This Is The’s World’s First Banner Ad:

This is almost the exact size, almost the exact resolution, exact ad.

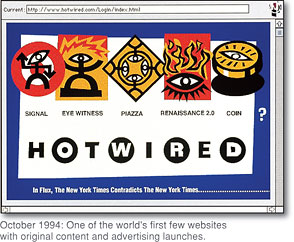

Of course, it’s not *technically* the first banner ad. There was no “one” first banner ad. Instead, there were around 12-14 banners, which all went live 20 years ago today, on October 27th, 1994. That was when the website HotWired.com first launched on the internet.

What follows is the story of the world’s first banner ad (or ads). This topic may not seem like something to celebrate, but think about this:

Basically, the majority of the web and the Internet are subsidized by ads.

The net as we know it today would not exist without ads. There would be no Google search. No Gmail. No Facebook. No Twitter. No Reddit. Nor any website that you can use basically for free…

Without advertising, that is.

Sure, there are huge sections of the Internet that function on a different revenue model (Amazon, eBay, iTunes and other things come to mind) but the vast majority of the online world we love is underpinned by an economic infrastructure of advertising.

This is the story of how that infrastructure was fist built, by the people who conceived and designed the very first banners.

Please note that this is a lightly edited transcript of an Internet History Podcast episode. If you want to hear the full story in everyone’s own words, please listen here. Otherwise, keep reading below:

The Story Of The First Banner Ad

But first, we need to start out by stipulating that the first advertising on the internet did not take place on October 27, 1994.

The early Internet, going back to the days of Darpa and Arpanet, had specific user guidelines outlawing marketing activities. In fact, commerce of any kind was verboten on the Internet until the early 90s.

These guidelines, of course, did little to stop enterprising persons from trying to promote themselves.

According to several sources, the first spam email was sent on May 3rd, 1978, when Gary Thuerk, a marketing manager at the Digital Equipment Corporation sent a mass email to 400 users he was able to collect from the ARPAnet directory, alerting them to the scheduled demonstration of a new DEC product. You can read the entire first spam email here.

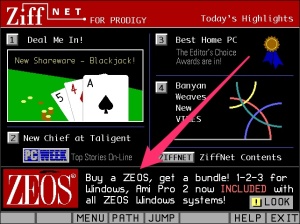

There were other early pioneers in the proto-online space. From its inception, Prodigy’s online service had banner-sized ads running at the bottom of every screen it delivered to dial up users.

In April of 1994, two lawyers from Arizona caused controversy by spamming 5,000 Usenet newsgroups with a message offering their services helping resident aliens get Green Cards.

But credit for the first true, linked, clickable, paid advertisement on the world wide web goes to a website called the Global Network Navigator, or GNN, which, in 1993, sold a clickable ad to a Silicon Valley law firm, Heller, Ehrman, White and McAuliffe.

Enter HotWired

The website that would truly bring advertising to the web for the first time would be HotWired, the digital publication launched by Wired Magazine.

Many people like to think, retroactively, that Wired Magazine was the herald of the Internet era. But, in fact, Wired launched and found great success several years before the Internet and the Web rose to mainstream prominence. Wired’s original manifesto centered around a cultural and social revolution that would be brought about by digital technology. But it had no more insight than anyone else at the time about what form that revolution would actually take. And so, for the first dozen or so issues of the magazine, references to the Internet and the Web were few and far between.

By 1994, however, the Internet was having its moment, and it was clear that if the “revolution” was happening anywhere, it was happening on the web. Wired co-founders Louis Rossetto and Jane Metcalfe were under pressure to jump on the web bandwagon. The thinking was that, rather than simply cover the revolution, Wired should actually join in an be a part of it.

Rossetto consented to create a web property with the stipulation that said property be more than just an experiment. The saga of Wired’s founding and funding had been a long an arduous one, and the magazine had only recently achieved financial breathing room, thanks to an infusion of cash from Condé Nast. Rossetto had no appetite to launch yet another enterprise that would bleed cash for years, as the magazine had done. So Rossetto insisted that, from day one, the web enterprise had to contribute meaningful revenue to its parent property. Rossetto was happy to give the web a try, but only if he could make it pay.

Thus, unlike the other early web startups that would soon flood Silicon Valley, the site that would become HotWired did not have the luxury of burning through cash before finding its footing. But how was HotWired to make money? Other early media properties like Time Inc.’s Pathfinder, Microsoft’s Slate.com and Salon.com would experiment with subscriptions and paywalls in order to generate revenue. It was thought that HotWired couldn’t go this route because Wired readers already paid a subscription for the magazine. The feeling was that it made no sense to charge loyal subscribers for a second, somewhat supplemental offering.

And so, when in early 1994 Rossetto recruited a former investment banker named Andrew Anker to write a business plan for HotWired, Anker settled upon the only logical revenue stream he could envision for the enterprise.

Advertising.

Andrew Anker

(Anker was a former partner at the boutique San Francisco investment firm, Sterling Payot, and had been instrumental in helping Wired raise money for its founding. At the time, Anker was the CTO of Wired, and would become the CEO of Wired Ventures, the separate corporate umbrella HotWired would launch under.)

My mandate was (…) We’re building a business here. We’re not building a project. We’re not building a product. We’re building a business. (…) He [Rossetto] was not going to do it [HotWired] unless it was done properly as a full-fledged business effort.

A lot of the things that we did, and that we’re credited for, were really not brilliant decisions, they were constraints. We had no choice. If I’m writing a business plan in March of 94 for an online business that has to make money, this is before SSL (…) there were no credit cards [online], no other way to make money but getting advertisers to pay.

Wired magazine’s recent success on the newsstand meant that the new website could call upon the mothership’s existing relationship with advertisers. The pitch was simple: come along for the ride as we try to pioneer this new medium.

Andrew Anker

We had a relatively small ad sales force at the magazine. We knew we were going to leverage that. AT&T, which had already been a big advertiser at Wired magazine had already said, ‘We hear you’re doing something online. We’re in.’ Jane [Metcalfe] who led a lot of the ad sales efforts came to me and said, ‘Great! What are they in for? What are we going to charge them? What are we going to sell them?’

The HotWired pioneers had little in the way of templates or examples to draw from for inspiration. There literally weren’t many other web publications at that point, and none, certainly, that were operating at the scale HotWired aspired to. In addition, little of the digital publishing technologies we are used to today were available at the time. So, HotWired made things up as it went along, and borrowed heavily from its print roots.

Joe McCambley

(Joe McCambley was a creative executive at an agency called Modem Media. One of his big clients was AT&T. Joe would go on to work at Digitas, AOL and found The Wonderfactory.)

I think, in hindsight, we talk about those days as if we had this grand plan and we were executing flawlessly, but a lot of it kind of happened accidentally, and serendipitously.

We didn’t really know anything. We didn’t know, you know, “What’s the color palate? What’s the K size that’s allowed for the banner? Where will it be placed on the page? What will the size of the banner be? What will it link to? If it does link to something, where will everything be stored?” We started the project with kind of like the classic white page of paper with nothing on it.

Andrew Anker

We had a very sort of linear approach at that point. There were no ad servers. We were writing everything ourselves, including the content. There was no CMS, no ad servers; there was barely a web server at that point. Brian Bellendorf, who helped get Apache going, was our engineer. So he was sort of simultaneously writing the code for HotWired and helping the Apache project give us a stable web server.

What we decided to do was sell one advertisement against one content section. $10,000 was a round number that made the numbers work, and we tried it and everybody sort of seemed to buy it. (….) We tried to match, as much as possible, advertisers to sections. So, when I was talking to [an advertising agency] they said, “Volvo is very interested.'”We said, “Great! We have this section called ‘On The Road” where we were going to send a reporter to go do something, on the road, and send in reports. One of the most famous ones was, he [the reporter] got into the Oscar Meyer Weinermobile and went across the country firing broadsides from the road. And that was sponsored by Volvo. We just—one by one—we matched up an advertiser to a section. There was no adserver; if you went to that section, On The Road, you saw the Volvo ad. If you hit reload you saw the same Volvo ad. It was sort of that simple at that point. There was no idea of targeting.

As the ad sales and technical development of the site itself went forward, word went out to advertising agencies that a new type of creative was being developed.

Joe McCambley

There was a big buzz at Modem… The web had already started. The Netscape browser launched, and there were rumors going around that MCI was going to doing some sort of amazing digital experience. When we brought that news to AT&T and AT&T was trying to figure out what their response would be… And then, about this time, we also started hearing rumors of Wired Magazine launching an online version and that there was going to be sponsorship involved… There was just this kind of perfect storm of events that created a sense of urgency around “We’ve gotta be doing something on HotWired magazine when it launches… gotta beat MCI to the punch. And it’s gotta be good.”

At the time, as you can imagine, there weren’t a lot of people who even knew HTML. So we did a search and we found a company in Westport, CT, named Tangent Design. It was run by a guy named Brent Hood. And he had a technology leader who was working on the IBM business named Otto Timmons. And Otto had been doing some work with a young kid that just came out of the MIT Media Lab named Craig Kanarick. Who eventually went on to found Razorfish. At the time, I think Craig was living on Otto’s sofa–or somebody’s sofa. I just remember thinking that he was this brilliant kid that really understood technology very very well, and I was wondering why he wasn’t already rich.

Craig Kanarick

(At the time Craig Kanarick was a young multi-media designer working with various agencies. He would eventually create The Blue Dot, which is credited with being the first animated website. For the HotWired project, Kanarick would design the AT&T ad, the one you see at the top of this piece. Kanarick would later co-found Razorfish, one of the first interactive web agencies.)

Somewhere in in the fall or the late summer of 94, they got a call over at Tangent from a company down the street… from Modem Media… explaining that Wired magazine was going to launch a new website called HotWired, and that on that site there were going to be ads from companies in the same way that magazines had print ads. They hadn’t quite figured out what the details were. But one of Modem Media’s clients, ATT, had either heard that MCI Friends and Family was having an ad… I don’t remember the exact circumstances around the media buy… but that they had bought an ad for ATT and they wanted to work with us to try and create this ad for ATT to go on the Wired website when it launched in late October 94.

Otto Timmons

(The man who had recruited Kanarick to work at Tangent was Otto Timmons, a VP at the firm. Tangent had recently finished work designing IBM’s first consumer website. Today Otto is a principal at 3GR in Los Angeles.)

Originally we approached IBM to do their banner ad, but their agency, Ogilvy and Mather, had already gotten that business by contract. Eight days before HotWired launched, Doug Ahlers from Modem Media called us and said, “Boy, have I got a great opportunity for you!” I thought, “Wow, that’s fantastic! When’s it due?” And he said, “It’s due in 7 days!” We actually finished the IBM website, slept for a day, and then started working on the AT&T ad for Hotwired.

Craig Kanarick

I happened to know the cheif technology guy over at Wired at the time. A guy named Brian Bellendorf . He was sort of sharing his time between Wired–the digital side of Wired–and a digital agency, Organic, that had opened up in the wake of all of this in the same building as Wired. They were collaborating a lot on these projects. I know Organic did a lot of these ads as well.

Andrew Anker

They [Organic] were a floor above us in the building… friends… we all hung out together. And so, when advertisers came in and didn’t have a website, we would send them to Jonathan, and Jonathan would then build those couple of pages that we would then host.

Jonathan Nelson

(Jonathan Nelson was the co-founder of Organic, one of the first interactive digital marketing and design agencies in existence. Organic would produce roughly half of the dozen or so campaigns that would launch with HotWired. Today, Nelson is the CEO of Omnicom Digital, the digital arm of the massive Omnicom advertising firm.)

What HotWired was doing was really the first Internet media company. Where they were saying, “Look, we’re going to put up content and it will be sponsored by you. Or, the advertising is going to pay for it. So what are we going to sell you? Instead of a print ad or a thirty-second spot, we’re going to sell you space on a web page.”

Once Rick [Boyce] sold that to AT&T. We were the guys that actually did everything else.

There were very few people that even knew how to build a website at that time, so we just got it done.

Otto Timmons

We didn’t have anything to go on. And I asked. That was sort of the second phone call with Doug. “So, what are we selling? What’s the ad concept?” And he said, “Well, we don’t have that either. So, you can really do whatever you want. It’s a blank page.” So we kind of made it up as we went along.

At the same time as the conceptual and technical details were being hammered out, the very first web advertising sales force was assembled to line up the brands that would join HotWired in this first web experiment.

Rick Boyce

(Rick Boyce was recruited to HotWired to form the first ever web-ad sales team. Brought on mere weeks before the launch, Boyce had to work quickly, but found there were more than a few brands eager to be on the cutting edge. Today, Boyce is head of corporate sales at the digital advertising company Quantcast.)

To be able to join a new medium at it’s birth, I felt like, boy, that puts me at the same league as the folks who joined television in the early days… newspaper, radio, etc. I saw it as being that important as a movement and something I wanted to be a part of.

I had no idea, from a technical perspective, how any of it worked.

We had in place a pretty extensive network of Wired magazine sales people. And this included a lot of folks you’ve heard of, and certainly have become famous in the digital media industry. People like Doug Weaver, people like Mitchell Kreuch, like Bill Peck, were all on the Wired sales team.

Andrew Anker

We made no commitments [to advertisers] because we quite frankly had no idea what to commit to. (…) They were doing it because they wanted to be part of the club, of pioneering this new medium. We all knew the money would be wrong. We didn’t know in which direction, but we knew we’d figure it out later.

Rick Boyce

I think when I joined we had maybe three or four advertisers committed. And then the next came in in pretty rapid succession after that. One gentleman, Steven Comfort–again, someone who’s pretty well known in digital media circles– (…) He actually placed four campaigns (…) and that was for two MCI business units, club Med and also Volvo.

Beyond those four, Modem Media brought in two–and that was the second AT&T division–and also Zima. We had a campaign from IBM that was beautifully done; that came out of Ogilvy in New York. We had a company called the Internet Shopping Network which was later acquired by the Home Shopping Network. Sprint. That was out of J Walter Thompson in San Francisco. We had another west coast company called Metrocom, which was setting up wireless LANs. And a number of others. In every case, early adopters, companies that really wanted to be a part of, and were committed to, the future.

We sold them [the banners] as sponsorships. They were, if memory serves, 12 weeks, $30,000. That was the launch price. We raised it in 1995. And there were no delivery guarantees or any kind of commitment about clicks. But that advertiser would own that presence persistently for that entire 12 week period.

Make It Up As You Go…

Again, everything being produced for the project was brand new. There weren’t any previous models to draw from. Everything was being made up as the teams went along. Schematics, design issues and other problems were solved on an ad hoc basis.

Andrew Anker

The size of the ad was a very–again–pragmatic decision. At that point, most monitors were 13 inches, sort of on the order of 640×480. Color was not something you could assume. Black and white was still not unusual. And so, when we were designing the first page, we took a sort of one-third/one-third/one-third approach. One-third for the advertisement. One-third for the masthead or the logo of the section that you were on. And then, one-third the beginning of the text. So you would see your ad, see what section you were on, and then start to have a little bit of a pull-in to the story itself.

Rick Boyce

They were all graphical image files. These were all static GIFs, there were no animations at the time. There was no way to animate a GIF. So every single ad truly was a static picture.

Joe McCambley

I remember having a big debate—and we probably argued for an hour or so—about whether or not it should even be a color ad. We knew we could make it smaller if it were black and white. We knew there was a large percentage of people out there that only had black and white monitors anyway.

Craig Kanarick

The tech, and the sort of specifications about where these things would appear and how big they were… were all sort of juggled about until almost the very end.

The size of the ad was really created because of the size of the browser at the time, and the scroll bars on the side, and people just trying to figure out exactly what would fit.

If I remember correctly, it was Matthew Nelson, who helped start Organic with his brother Jonathan. And he worked with Barbara Kuhr and Rick Boyce and they were really creating the specifications. What they said was, “Ok, we’ll make this ad, it will sort of run the full width of the screen and then you’ll get an image, and that image can be linked to something.” They were designing for Mosaic and maybe an early version of Netscape at the time. And they started to play around with it and realized that somewhere around 460×60 was the right number [in pixels]. But then, the browsers at the time automatically put a two pixel blue box around those ads. So they shrunk it down to 546×56.

Jonathan Nelson

It’s hard to imagine this because webpages have become relatively sophisticated, compared to that era. At that time, you couldn’t actually even center a banner. Everything was flush left. So you had sort of a margin on the left and everything was just jammed up against it. You would make the banners only two or three different colors. And you couldn’t have complex graphics in them because everybody was on modems at the time. Bandwidth was extremely limited.

Rick Boyce

One of the things that the slow connections created–this is an unfortunate side effect of the slow connections at the time–was that the ad units were pretty small. (…) They were small on purpose and they were small to make sure that the file sizes were small and those pages would load as quickly as possible over a modem.

Joe McCambley

Honestly, once we determined what the size of the banner was going to be, we had more conversations around traditional billboard advertising. What does it take to make a billboard successful? Try to keep your language down to seven words. You’ve got to try to have some sort of visual that will stand out and capture people’s attention. You’ve got to offer some sort of a benefit. I think we broke some of those rules.

There was a fair amount of handholding involved, both because the medium itself was brand new, but also because a lot of the brands weren’t sure what these new ads were supposed to do, exactly. For example: A web ad could be clicked on. But once clicked, where were the users going to go? Many, perhaps most of the brands who had signed on to be sponsors, did not even have websites at this point. So, HotWired solved this by building landing pages for them.

Andrew Anker

We actually mandated that those ads clicked to pages on our site. Because, we just didn’t want to have any kind of breakdown in experience. The way it worked, for that $10,000, you got your ad at the top of the page, and then you got 3 other pages on our site. From there you could link off to your own site. You could do whatever. There were definitely advertisers who only had the micro-site on HotWired that we provided.

Rick Boyce

The challenge became, for some of these advertisers, was that after they made the commitment to buy the space on HotWired, they really weren’t sure where that was going to link to. (…) I mentioned IBM earlier, for example. IBM certainly had a comprehensive website in 1994 but it was designed for a much different purpose. It wasn’t consumer-facing, per se.

Craig Kanarick

Not only were there not a lot of really big corporate websites, at the time there was really a debate whether a corporate website would actually be the thing that people wanted. Like, who would want to go to a website like pampers, where they’re just going to talk about diapers all the time? I think Zima had a website. They were one of the original advertisers. Zima, ATT, Sprint, Timex, MCI, Volvo… and I think a modem company called Zircom.

Joe McCambley

Yeah, really nobody had a site then except maybe Zima. I think they launched their site in conjunction with those ads running.

Craig Kanarick

It’s interesting because there really was no “one” single first banner ad. There were actually… depending upon how you count, there were six, or eight, or fourteen. There were a bunch of them that were all sold at the same time.

You Will…

In retrospect, we like to think of the AT&T ad as the defacto “first” banner ad because it makes for a better story. For one thing, there was the copy: daring the first web users to “click here”! That’s cheeky. And prescient. Also, since all the banner ads launched simultaneously anyway, why not give the credit to AT&T? The overall narrative it fits into is so fun.

It’s weird to think of it this way, but in 1994, AT&T was sort of a fledgling consumer brand. The Bell system had only been broken up ten years previously, in 1984. AT&T was in, what for it, was an interesting new position. It was suddenly forced to compete with upstart rivals like Sprint and MCI for the hearts and minds of consumers. The “Reach Out and Touch Someone” ads of the late Bell era had evolved into a new nationwide campaign that could be called the “You Will…” campaign. You may remember the campaign because it was ubiquitous in the early 90s. Narrated by Tom Selleck, and directed by David Fincher, the eventual film director, the ads moved AT&T’s branding away from personal connection and toward a futuristic utopian world where reaching out and touching someone was a ubiquitous and magical occurrence.

The ads all had the convention of “Have you ever done x?” followed by the assurance that, “You will. And the company that will bring it to you is AT&T.” So, for example, one ad had a mother (Jenna Elfman) tucking her children in via video-call (“Have you ever tucked your baby in from a phone booth? You will…”) and another showed in-car GPS navigation, pretty much as it exists today (“Have you ever crossed the country without stopping for directions? You will…”).

Craig Kanarick

They showed this sort of Jetsons future of the world… many, if not all of those have come true. But at the time it was really this sort of fantasy about how the future is going to be amazing.

Here is a compilation of the entire series below. Marvel at how many things this campaign got exactly right. Ebooks. Mobile tablet computing. Videoconferencing in your bare feet. Netflix. Software agents like Siri. Even wrist computing (“Have you ever gotten a call, on your wrist?”).

And so, this is the milieu that the AT&T ad grew out of.

Joe McCambley:

We knew that AT&T was spending hundreds of millions of dollars on the “You Will” campaign. There was incredibly high awareness of the campaign. So we wanted to take advantage of that.

Bill Clausen

Bill Clausen

(Bill Clausen was an Advertising and Communications Manager at AT&T and he was pushing hard to move AT&T into new interactive technologies for marketing purposes. Part of that remit found him working with Modem Media on various initiatives.)

We [AT&T] were having a very difficult time competing on price. (…) MCI was poking at us on price. And we were doing everything to play to our strength, which was: think of all the wonderful things that we’re helping to bring to you. From the whole “reach out and touch.” The emotion appeal of that. That we help connect you to the people you want to talk to. Into the “you will” campaign which is all about (…) we’re helping to bring these new, positive, futuristic things to life for you. That will make your life even more incredible. We’re at the forefront.

A lot of Bill’s efforts involved getting AT&T to experiment with advertising online, especially with the early online services like AOL, CompuServe and Prodigy. But he was meeting with the age-old brick wall of corporate inertia.

Bill Clausen

It’s the typical, big company, very established, don’t rock the boat, we’ll get to it, type of thing. (…) Anyone who’s ever championed anything in a big company will all understand the blood, sweat and tears that goes into something like that. When you firmly know that it’s the right thing to do, but you have to convince the establishment that they should do it.

But…

Bill Clausen

Competition can be good, right? What happens is, we knew that something was happening on the internet. (…) All of the sudden we hear there’s a threat from MCI. There’s this property called HotWired that is about to–for the first time ever–allow advertisers to advertise. And they’re booking space. Still trying to figure out what that advertising is going to be, but it looks like MCI is going to be there. That’s all we had to hear. That’s all I had to hear. All the pushback that I ever had about business case… all the other things… the gauntlets you have to go through… this changed everything. Once it was explained to the powers that be what was going on, I got the green light to go. Unfortunately, once we found out about this, it didn’t give us a lot of time. Less than a week?

Enter the creatives, like Joe McCambley, Otto Timmons and Craig Kanarick.

Joe McCambley

He [Bill Clausen] placed an enormous amount of trust in us. There wasn’t a lot known about the web. There weren’t a lot of facts we could give him and I think his direction was, “To the extent that you can, tie it in to this campaign that we’re spending hundreds of millions of dollars on. And if you link to people, make sure that you link to people that our band wants to be associated with.”

Bill Clausen

Full credit to Joe as the leader of the ship here. He took it and worked crazy hours to make this happen. I still remember being up with him until I think it was like two or three in the morning. It was nuts. It was crazy stuff.

Joe McCambley

Honestly, we would have so many late night conversations with the brand people at AT&T. Literally, two in the morning for months prior to this where we were just talking about the web and what it could mean, and what it could mean for communications. And what it would mean for people.

But how could the ad tie in to the whole “you will” ethos of bringing amazing new things into people’s lives thanks to technology? Sending people to some corporate landing page that encouraged you to sign up for long distance service seemed to be missing the point. So the team hit upon the idea that the AT&T banner would help show people the amazing things that the web was making possible. If a user clicked on the ad, they would be taken not to an AT&T sales pitch, but to virtual art museums around the world.

Otto Timmons

The three of us sat down and we kind of said, “What are we doing? Who are the users on the Internet? Who are the customers? What are the customers of HotWired going to be? What speed are these people going to be coming in at? What’s the culture?”

One of the questions is, is it ok to actually sell something [on the web]? We said, you know, these people are used to not being confronted with commercialism. The way that the Internet worked was, people creating software and putting it in the public domain. We said, “We need to do something that is, in that spirit.”

You know, this should be like a corporate sponsorship of a PBS show. Or like, a corporate sponsorship of a cultural event or a museum exhibit.

Craig Kanarick

We decided that what we would do is help people discover the amazing part of the internet. We thought that what was awesome about the internet was that the future was already there right now. We decided that what we would do is expose people to all the great art that was on the internet. So if you clicked on that banner ad, you were taken to a landing page where you were given a choice… there was a map of the world… with maybe five or six dots on it…that represented art museums that had websites. So, one of them was the Louvre. I, really off the top of my head can’t remember what the other ones were, but there were four or five, real-world museums that had put part of their art collections online.

Otto Timmons

We were sponsoring a section of Hotwired called Retina, where there’s all sort of interesting cultural things that are going on. And we though, what can we do that would be a plus for that section. I had just recently read an article about museums that were online. I was surprised the Lourve had a couple of websites already. And they had these jpegs and images online.

Joe McCambley

They [AT&T] felt that [way back] when they launched their first-long distance network [in the 19th century] that they had an obligation back then—that they fulfilled—to teach people how to use phones and how to communicate. So, they asked us to try to figure out a way to do the same thing with the Internet.

The reason that we wanted to link to the museums is because A) museums had decent content that we could link to, but B) we wanted to give… we were sponsoring the arts section of HotWired magazine… so it made sense to link to museums. We wanted to transport people to places they might not otherwise travel.

Bill Clausen

We thought, this is so good. If we can continue this “you will” feel, if we can put something there that is compelling… that they click on it, and now, literally opens up the world to them. (…) We’re in [a section of HotWired] called Retina, which is all about this digital eye candy. We really don’t have the content from AT&T that we can serve up here and kind of say “Here’s our message.” That didn’t exist yet. We don’t have a website. We don’t have content that we could promote ourselves [with].

The AT&T banner would link to the websites from Lourve, the Andy Warhol museum, the Library of Congress and others.

The constraints of the technology of the time, the lack of previous examples to draw from, and the mandates from the client had forced the team to get creative. But there was one more wrinkle that seemed like it might scupper the entire effort. In the end, it merely served to nudge the team in what turned out the be the right direction.

Joe McCambley

We had been working all weekend, through Monday and Tuesday. It was either on Tuesday night or Wednesday night, and I think that the assets for the banner had to be to HotWired by Wednesday or Thursday. So, it was the night before the assets had to be turned in. It was about ten o’clock at night and we had a brief thunderstorm. Power goes out. All the computers at Tangent, where we were working, shut down. And Craig sort of went ballistic. I can remember at the time thinking he was unreasonably upset. So I said, “Chill out. It will be ok. The power will come back on. We’ll get back to work.” And he said, “No! You don’t understand! I never saved anything!” And I said, “You’re a graduate of the MIT Media Lab! We’ve been working for four days straight and you never hit Control-Save once?” But within a few seconds, he settled down, hunkered down, got back to work, and within a few hours, he just rebuilt everything from scratch.

But there was an unintended consequence that came out of that. (…) We didn’t have time to rebuild the banner in the way we originally conceived it. That’s why we landed upon something very simple like “Have you ever clicked right here?” A few months later, when we were doing A/B testing at Modem Media, we learned that if you put the words “click here” on a banner, sometimes you could increase the click through rate by like 50%.

Craig Kanarick

One thing that you’ll notice is that there’s no actual ATT logo in the ad. And that was due to AT&T being uncomfortable with exactly what was happening. They weren’t fully convinced that this was such a great idea.

(…)

At the last minute, ATT said, You know, maybe we should actually find out who these people are, so, let’s put a survey up on the site as well, and ask them a little bit about their long distance, or something to that effect.

But the ads seemed to work beautifully, as they, wound up generating behavior numbers from web users that marketers would salivate over today.

Joe McCambley

We did little research at the time, but the research we did with consumers, you would see that, you know, they were just clicking all over the page to figure out what was clickable. Now we all know what a hyperlink is. Now we all know what a button should look like. Now we all know what the standard conventions are. But at the time, they hadn’t really been invented. People just clicked on anything to see what might lead them somewhere.

Otto Timmons

People didn’t know that it was an ad. You know. “Have you ever clicked your mouse right here? You will.” Maybe they recognized the You Will typography, maybe not. Banner ads had been on the Prodigy service, but they were at the bottom and they were big and ugly. There was nothing like this. Nothing at all. So, we probably got a lot of click-throughs from people who were curious.

Craig Kanarick

I don’t know the numbers off the top of my head, but it [the click-through rate] was a ridiculously high number. I don’t know if it was 50% click-through or whatever it was. It was a huge amount. It sounds very impressive. But you have to remember that no one was exposed to ads at the time, so it wasn’t clear that people understood that that was going to take them somewhere that maybe they didn’t want to go.

I would like to think that it was because I designed something that was incredibly beautiful, and that our copywriting was so amazingly compelling, but I think the truth is that it was also a time when people were not sort of inured to ads. And not angry about them.

Otto Timmons

In the beginning, every week I spoke with Brian Bellendorf over at HotWired. He was the HotWired webmaster. I would ask him, “So, how’s our ad doing?” and he was like, “Yep, it’s still number one.” It was basically the number one ad the entire time it was running up there. I think it ran for a little over 10 months.

Joe McCambley

I don’t think this banner, the AT&T banner is unique. I think a lot of the banners on HotWired got extraordinary click-through rates. For about the first couple of weeks it bordered between the high 70s and low 80s [in terms of click-through percentages] for about 2-3 weeks. It settled in for about a two, to two-and-a-half month period in the 40s. Around 44% is what Bill told me. And then it slowly declined over time.

Bill Clausen

And then we’re hearing that we’re getting like, outrageous–again, we don’t know what to measure it against–but, for every two people going to it, a person’s looking at it! They’re clicking on it. So we’re getting 40-44% click-through rates.

Rick Boyce

They were high. I remember some of the reports that we saw click-through rates as high as 50%, maybe even a little bit higher than that. One of the reasons why, I think–quite literally–there were a lot of businesses people that were thinking about their own [potential] Internet-supported business looking at our site. We launched with advertising ten months before Yahoo did. We launched with advertising seven months before Excite and Lycos and some of the other big search guys. And so, there were a lot of businesses that were publishing on the web that hadn’t yet explored advertising and hadn’t really thought through advertising as an opportunity. And I think we became a great place for others to go and just kind of get some experiences with internet advertising and what it could look like and how it might work. I think, certainly, there was some consumer interest in those campaigns; but my guess is most of it was business people who were exploring to help them further develop their own business plans.

Andrew Anker

I was reading a thread on Quora where people were saying it was 78%, and quite honestly, I don’t remember. And I don’t think those people remember either. They [the click-through rates] were ridiculously high. The first couple of weeks people clicked on everything. This was really not just the first advertising on the internet, but the first real proprietary, media-created content. It was something that people were clicking on every single page. And ads were just as interesting content as our content. In the early days, we really did have on the order of 70% to 80% click throughs on a lot of the ads.

I would say for the rest of 1994, and well into 1995, if someone’s click-through rates fell below 2%, we knew the banner wasn’t a good banner and we had to help them to make it better.

The Launch Heard Around The World

HotWired’s launch sent reverberations around several different industries. First, the site itself proved that a professionally produced content site was possible. HotWired would serve as inspiration and impetus for other sites that would soon follow: CNet, Salon and Time Inc’s Pathfinder.com, among others.

Also important: HotWired showed that advertising could be a viable business model for websites and web services of all types.

Rick Boyce

Lycos, and Excite, I think, launched with advertising–probably InfoSeek too–in the spring, summer of 1995. So, I would say, Spring/Summer of 95, advertising was starting to take off. Netscape’s IPO hit in August of that year. Yahoo started selling advertising in November of 1995. So, within a year of HotWired’s launch, to me, it was starting to feel very very real.

And just as crucially, for the first time, major brands began looking seriously at web and digital advertising as a completely new channel to funnel their advertising budgets into.

Rick Boyce

I think it was an incredible success for the brands. And certainly the PR was huge. We got a lot of coverage as a company, the brands got a lot of coverage as well. They were typically mentioned.

Bill Clausen

It was perfect. It reinforced our brand. It reinforced “you will.” (…) We know what you’re trying to do. You’re trying to reach out and get there. We got you there.

Rick Boyce

We did a lot of other things first as well, and one of them was the first band effectiveness study. We were showing the world that internet advertising worked to drive brand awareness and to change people’s minds about brand and brand perception.

Indeed, it wasn’t just in the areas of media and advertising that HotWired experiment blazed a trail. As mentioned previously, a little-known story is that the initiative that would eventually lead to the Apache web server had its roots in HotWired’s launch as well.

Jonathan Nelson

The original Apache web server used to sit underneath my desk. The reason why we developed it was quite simple. The CERN software, which was really the server that we used, was open source. You could grab the source code for it. Most companies, that had a little bit more money than we did, they would essentially run one web server per site. And so, if you had Volvo, and Club Med and AT&T and MCI, which we were all hosting, at the same time… We didn’t have enough money to have six different servers for six different sites. So, we hacked the original CERN source code so that we could host multiple websites on a single box. On a single PC. We became sort of famous for that hack. And people were asking us for copies of it. And then we said fine, we’ll put our patch to the CERN web server. Hence, the joke, A “Patchy” web server… we’ll put that up in the public domain. (…) And that’s how the Apache server developed. And Brian Behlendorf, and Cliff Skolnick, who were two of my partners in Organic, really went off to develop the Apache server. And now it’s got, what, 60-70% of the Internet server market?

And while it’s well known that the first web ads were pioneered by the HotWired team, work done at HotWired a few years later can possibly lay a claim to being the first mobile ad.

Rick Boyce

In 1998, we put the first ad ever on a mobile device, and that was on the Palm Pilot 5. You might remember, the Palm would sync to your computer and you’d push a little button and it would sync the content of certain Palm deployable content with your Palm Pilot itself. And that was for Hilton Hotels. It was Wired News on the Palm Pilot.

Twenty years on, the men who brought the Internet the banner ad generally look back on their work with pride, if sometimes a bit sheepishly.

Otto Timmons

You know, you get the normal, “You did that? Thank’s a lot!”

Craig Kanarick

I still sometimes chuckle when I see a url at the end of television commercials, cause I still remember trying to explain to people what a url was.

Rick Boyce

I do look back at it with pride. And really, with gratitude. Literally, the best job I’ve ever had.

Joe McCambley

I’m proud of that first banner, and I’m proud of the results it generated. But I think that, when I look at the banner today, it’s representative of the dark ages of advertising. This is the year 1300 in advertising if the banner is the best we can do. I feel great hope. I think that just like the dark ages, it’s going to be followed by a renaissance.

Bill Clausen

The banner ad as kind of Internet, pre-historic, writing on the wall, was hugely important. But from where we are today? Twenty years later? I have to say I’m a little disappointed.

Twenty years later, I think it’s time for the next evolution or revolution of what advertising and marketing needs to be on the Internet.

Otto Timmons

I’m enormously proud of it. I think that one of the things we tried to do is, we tried to show the rest of the industry that this is how you can do it. You know, that you don’t have to sell something. It might be better, in fact, to not sell something. And that would be a good way to not piss people off. But unfortunately, that didn’t—nobody looked and did that. So I think that’s a little bit sad that they didn’t follow our example.

Joe McCambley

When I look at the legacy… as important as it is, I hope that’s not the most important thing that ever is associated with me. (…) As important and valuable as that banner was, I think, to not let it be my only legacy. I guess there’s ambivalence.

Special Note: Craig Kanarick and Otto Timmons have set up a website with more info on the first banner ads. You can check it out at www.thefirstbannerad.com

Enjoy Geeking Out About Internet History? There’s WAY More Where That Came From!

Subscribe To The Podcast

[…] of when the first banner ads began appearing on websites. In the form of an oral history, Brian McCullough at the Internet History Podcast takes a fun trip down memory lane with the people who were at ground zero of the commercialization […]

[…] of when the first banner ads began appearing on websites. In the form of an oral history, Brian McCullough at the Internet History Podcast takes a fun trip down memory lane with the people who were at ground zero of the commercialization […]

And just look at the BILLIONS that newspapers are making in online ad revenue today. . .

[…] Internet History Podcast has a great audio and text writeup of those early online advertising days. Just about everyone […]

[…] Brian McCullough, host of the Internet History Podcast […]

[…] On The 20th Anniversary, An Oral History of the Web’s First Banner Ads – Brian McCulloch, Intern… […]

What a “throwback” to read this article and see the image of the Prodigy screen shot under the headline “The Story of the First Banner Ad” with the ad from ZEOS…I sold that ad to ZEOS in the mid-1980’s as a sales exec at Prodigy. Great memories of the beginning of digital advertising!

[…] Looking back on 20 years of web banner ads […]

[…] […]

[…] is a detailed look at some other early Internet ad campaigns. Today marks the 20th anniversary of the first banner ad […]

[…] that the first online ad went live in 1994, yet, 20 years later we continue to find ourselves investing time, resources and budget into […]

[…] that the first online ad went live in 1994, yet, 20 years later we continue to find ourselves investing time, resources and budget into […]

[…] that the first online ad went live in 1994, yet, 20 years later we continue to find ourselves investing time, resources and budget into […]

[…] Odličan in-depth intervju sa svim glavnim akterima ove priče, iz kojeg i potiče najveći deo gore navedenih detalja, možete pročitati ili preslušati na stranicama internethistorypodcast. […]

[…] first spam email in 1978. A law firm bought the first text web ad in 1993, and AT&T bought the first banner ad in 1994. Google sold the first search ad in 2000, the same year a Finnish company sent the first […]

[…] first spam email in 1978. A law firm bought the first text web ad in 1993, and AT&T bought the first banner ad in 1994. Google sold the first search ad in 2000, the same year a Finnish company sent the first […]

[…] decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had […]

[…] decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had […]

[…] brilliant decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had no […]

[…] brilliant decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had no […]

[…] brilliant decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had no […]

[…] brilliant decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had no […]

[…] brilliant decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had no […]

[…] brilliant decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had no […]

[…] brilliant decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had no […]

[…] brilliant decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had no […]

[…] brilliant decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had no […]

[…] decisions, they were constraints,” then-Chief Technology Officer for Wired Andrew Anker told the Internet Podcast in 2014, while noting the lack of secured payment technologies for credit cards at the time. “We had […]

The First Spam Main in 1982, Facebook Launch First in 2000, Google is the First Popular Search Engines

I worked at Mondo Media, a digital studio that was hired by ad agencies in San Francisco. Our artists created “banner ads” for Prodigy back in 1992. They were created in 8 bit (NAPLPS) graphics with multiple story-telling “pages” or “banners,” although that wasn’t a term used at the time. They ran at the bottom of the screen and depicted Disney characters, travel destinations, cars, and other artistic elements.

I do believe these truly were the first banner ads. Here is a collection on Flickr for The Prodigy Preservation Project, by Benj Edwards https://www.flickr.com/photos/149332336@N06/albums/72157678942026584

[…] Source: Internet history podcast […]

[…] Heller, Ehram, White and McAuliffe who was sold a clickable ad by Global Network Navigator (GNN) around the same time when hotwired.com placed AT&T banner ad on its […]