Summary:

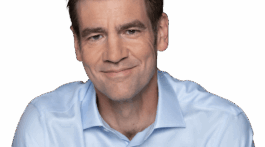

Lou Montulli is a web pioneer. In 1991 and 1992 he co-authored a text web browser called Lynx with Michael Grobe and Charles Rezac while he was at the University of Kansas. This web browser was one of the first available and is still in use today.

In 1994 he became a founding engineer of Netscape Communications (employee number 9) and programmed the networking code for the first versions of the Netscape web browser.

He is also responsible for several browser innovations, such as HTTP cookies, the blink tag, server push and client pull, HTTP proxying, and the implementation of animated GIFs into the browser. While at Netscape, he also was a founding member of the HTML working group at the W3C and was a contributing author of the HTML 3.2 specification. He is a member of the World Wide Web Hall of Fame.

Lou was also a co-founder of Epinions.com. He was the CEO of Memory Matrix, and when that company was purchased by Shutterfly, he served as Shutterfly’s Vice President of Engineering. He is currently the co-founder and Chief Scientist at Zetta.net.

- More about Lynx here.

- Here is the famous fishcam!

- Here is the post we discuss where Lou lays out the reasoning behind the birth of the browser cookie.

- The birth of the <blink> tag.

And a fun photo of Lou from back in the day:

Transcription:

Brian: So you’re born in DC, is that right?

Lou: I was actually born in Los Angeles. My father was in Air Force for 23 years. I moved all over the country. I was in Los Angeles, Albuquerque, Ohio, New York, ended up eight years in Washington DC, just outside Washington DC in Fairfax Virginia and ended my early schooling there through the beginning of high school and my father retired at that point, and we moved to Wichita, Kansas. So I ended up in Kansas for my final years of high school and ended up going to the University of Kansas after that.

Brian: That was my next question how you ended up at University of Kansas. I’m assuming your degree was computer science.

Lou: It was a originally an Electrical and Computer Engineering and then I switched to Consumer Science a few years in because I felt better suited what I was passionate about.

Brian: So is that where you got interested in the Internet or the web and in general at that point?

Lou: I was working at the University of Computer Center and originally I came in and was changing tapes and doing a lot of a menial chores. I kind of work my way up to doing Computer Support and helping professors and students figure out computers in general, a lot of silly questions on interesting ones I and we had an ongoing project that had been sitting on the back burner for a couple years, which was to create an online information source. This is going to be an emerging time when putting information out on the network was starting to become possible, and at the time the state-of-the-art was either FTP, which was very text oriented or there’s program called Gopher and Gopher was the first easy-to-use way of accessing network, accessing information over the network.

But it’s major limitation was that it simply provided a list of data, you go to one page, it will provide 5 or 10 choices that were number and you would choose the number and you go down to a series of list and they would get to a final document format and that document might be text or something else, images, other things. There wasn’t PDF or any of those sort of things around that time. There were Word documents and Excel documents that sort of the thing, the very basic kind of Computer Documents that we know of today and I set out to work on this project, someone accidentally. I had seen this product called HyperREZ which was a local hypertext browser which I became fascinated with.

I have never seen hypertext before that and saw there was a really interesting medium for connecting documents together and I thought that this was a much better method for browsing documents, then Gopher, so I started really a prototype project where I merged the user interface of HyperREZ to Gopher, which was a way of getting to the documents over the network and I created the product called Lynx in a prototype format for couple of days by merging these two separate programs together and started working on the Lynx project. I get to go ahead from the management of Computer Science and Computer Center there to work on it and I started working on that for about year and created a hypertext program that used Gopher as the backend Network Protocol.

So about year into this started hearing about this other project that Tim Berners-Lee was working on and that Marc Andreessen was working on simultaneous call the web which actually did the exact same thing but use different protocols, so use HTML and HTTP instead of Gopher and basically this really primitive hypertext format, which I had come up with. We’ve been essentially working on very similar things in parallel and I realized that an ecosystem is stronger when you have multiple people working on it. So what I did is I took Lynx and added the capability for it to process HTTP and HTML, and then have something that worked within the ecosystem of what was being called a web at this point.

Brian: At this point, when I find it in articles it’s always referred to as a text-only browser, so it gains browser capability, but it still at this point text only, is that right?

Lou: Yeah, the web was text only at that point as well. There was no images, there was nothing else. The actual interface for Lynx is on terminal systems. It is rare to have terminals that can provide image capability. So you might see that X Windows, which is a terminal as well but most of the users for Lynx were on text terminals through PCs and other things. At that time there was a lot more VT 100 displays and that sort of thing connected to mainframes to access some UNIX systems that sort of thing.

In fact, at the time that that the web really started take off, we don’t really have strong numbers for this but I think Lynx was probably the most used program on the web that at that time because people actually had access to it. It was really popular among universities and students at that time generally had access to computers via Mainframe and PCs connected to Mainframe Computers because it was rare to have a regular PC connected to the Internet that could have a standalone web browser to it.

Brian: Yeah, I actually don’t have in front of me but I found a link to something that was estimating the size of browser usage I guess a year into Mosaic and Lynx was still right up there with Mosaic at that point, at least according to the estimates.

Lou: Yeah. And also the first version of Mosaic was X Windows and almost nobody has X Windows access.

Brian: Right, right. Exactly. So Mosaic was popular and X Windows, but it didn’t really take off until the Mac and Windows versions came out, is that correct?

Lou: Exactly. What Mosaic was, was incredibly beautiful platform that showed the potential of the web and so seeing it on X Windows gave it a lot of the SaaS and people get excited about and then as the ecosystem filled in, the other browsers Lynx, Cello, Mac Mosaic and Win Mosaic helped give people access to it all over the world because as I said, very few people had X Windows terminal.

Brian: So at this point have you crossed paths with the NCSA guys and Berners-Lee on message boards and forums and things like that?

Lou: Yeah, as soon as I saw the release of X-Mosaic from Marc, I realize the potential for me immediately was I wouldn’t have to write this X Windows version because ironically, I was working on X Windows version of Lynx at exact same time so the timing was kind of perfect and I said, “Oh well, Marc’s written this thing, I don’t need to write another version, saved myself a bunch of time.” So I reached out early on, we started communicating fairly regularly within a few months time and as I was working… so at that time, the web protocols and such were supported by an open source library that came out as the web project that Tim Berners-Lee was running at CERN, so we were essentially using the same open source libraries and I started working on those libraries pretty extensively to improve their support for various other protocols like FTP, ways and other things. Marc and I were communicating kind of constantly on improving the library and making the back end support for these protocols much better.

Brian: Yeah and actually a lot of archives of those messages are online. If you are not around for a minute, if you know that.

Lou: Yeah, there is a message board called www-talk.

Brian: Right, exactly.

Lou: Which was the first one and then there was a another one because that one we got really popular among the general populace, so we created another one for developers only, which was a little bit more exclusive. Not like something you really wanted on it necessarily, but just for the people who are actively working on the development of the code.

Brian: So then the first time that you would’ve met Marc or any of the Mosaic guys was at the Web Developers Conference in Cambridge in 93.

Lou: Absolutely yes and that was sponsored by O’Reilly. It was a great opportunity for us to get together to discuss some topics that had been somewhat controversial and move the results.

Brian: Was one of those controversies the whole idea of adding images to the web?

Lou: Yeah, there wasn’t definite schism between us young kids and especially Tim Berners-Lee who I wanted to keep the web essentially, lowest common denominator all the time. I wouldn’t say that he was opposed to adding images and other things but he was opposed to the kind of methodology of which was going about wanted to make sure that everything was accessible. So we had a bunch of discussions around at the conference and came up with some interesting ideas, that is where the idea of ideal alt text came from adding textual descriptions of the images so that can be shown in place or as the analysis used as the tool tip.

We also you don’t would know this now but back then the HTML was incredibly primitive in terms of what it could actually markup and there was no way to even do line break. I remember we had the a line break, the BR tag at that point, which is hard to imagine that it did, it never existed but it really wasn’t any really presentation mark in HTML at time because Tim from HTML world had wanted to add essential style sheets. Early on, it was just the style sheets being so complicated were what wasn’t necessarily practical thing to do very quickly.

Brian: So Mosaic takes off and is there any discussion about maybe merging Lynx in Mosaic or maybe you heading over the NCSA or anything like that or you still staying in Kansas at this point developing Lynx on your own?

Lou: I was still in Kansas of developing of my own. We brought on another staff member who is working on virtual links for DOS and we released that. I never consider going to NCSA, the working relationship we had our e-mail is certainly working fine and things were also developing very rapidly. Marc left the project very quickly. He moved to California. I was close to graduating, so I was planning my exit, regardless and the certainly one could see that the popularity was taking off and that there was the commercial potential for things in the future and I had always in the back of my mind, and even beginning of the project thought, well I’m a releasing this thing so that I can gain some exposure and experience, so that I can go on and actually get a job, just eventually need to make some money.

I didn’t know I was going to be starting a company, but I knew that would be something in the tech career.

Brian: So that leads us to who gets in touch with you to start the recruiting process for Netscape, is it Marc or Jim Clark? Actually before you answer that Jim Clark says in his autobiography that you had a Racquetball Tournament in Kansas City or something so they contact you and you fly out?

Lou: So I was at the Intercollegiate National Racquetball Tournament down in Arizona and it’s a weeklong tournament. So I came back from that and had an e-mail waiting for me. Back before you can check e-mail on your phone and that I had a phone message, I think it was just a phone message not an e-mail. Maybe was an e-mail as well. I ended up calling Jim back, got his personal assistant instead of Jim and basically the message was Jim and Marc are going to fly out to Illinois and want to talk about starting a company, would like you to join him there and they’re going to meet the very next morning. This was like 1 in the afternoon, so basically I just got to flown in from Arizona, came from the airport to the office so I got back into my car, drove back to the airport and bought a ticket to Illinois on the next flight out which was a little stressful as a college student. I don’t know how close you are to college.

Brian: No, I was going to say. Yeah, I would hope they at least reimburse you or something.

Lou: Yeah, the most I’ve ever made it in salary at that point was $8000 a year. Basically living cheque to cheque and I remember asking his assistant, so you sure that Jim can reimburse me on this because I really don’t have the kind of money that I could just hop on to get on flight on the same day because they are always report time is expensive, but fortunately my credit card had enough on it that I get the flight and I actually ended up beating Jim and Marc out there because they get stuck in a snowstorm, so got there a few hours ahead of them.

Brian: So that the legend is that they do the interviews and the recruiting pitch at a pizza joint, or something like that. What you remember how that went down?

Lou: Yeah, I think we were actually in the hotel lobby but that kind of lounge if I remember correctly. It is little hazy, so I wouldn’t contradict what they said. We basically got together and started talking about what we could do and the idea of creating company around commercializing the web. And this is what we’ve been doing for the last couple years, so there was certainly no disagreement. Mostly we were talking about potential and how awesome it would be. And then we did have individual meetings with Jim. It’s hard to say whether what was the purpose of that was. I think Jim was selling us and also trying to make sure that all of us weren’t a little crazy because it is the first time meeting us, so there was definitely some selling going on. Jim talking about things which to our story seems incredible and unbelievable but he is very convincing guy and passionate. I remember walking out of that meeting just being incredibly excited about the opportunity and how wonderful thing it going to be in the beautiful land of California.

Brian: Right, I was going to say. I mean there was no hesitation on your part. Today kids leave college, go out to California and dream of becoming millionaires and stuff. And I know in that case wasn’t the first startup startups, but you know the template for going out and starting a web company, you guys made that template, so there wasn’t a little bit hesitation there. You were just excited there. Do you remember what you felt like about that?

Lou: Well for me the opportunity was just at a perfect time, perfect opportunity. I was already out job hunting and I have done several interviews in Intel and other places. And I had gotten some really good offers and way beyond what I thought I was going to be making right after college. Back then a fantastic job at college would be $30,000 and I was stoked. People were offering me double that. How could that be, this is fantastic, so future felt really bright. But I did really, really love what I was doing on the web and the idea to continue working on that with the luminary from the industry and the folks that I knew were already great programmers and had really pull up something amazing was… I mean I really never had a second thought about that. It was everything lined up. This was just the perfect opportunity at the perfect time. There was never a question from in my mind that I wouldn’t go do that.

Brian: So actually jumping ahead to California then…so from day one is it a plan to do a better browser or what was it still sort of up in the air, you’re going to do something on the web but you didn’t know what it was yet? Was the browser the plan from day one is my question.

Lou: The browser was the plan from day one, so maybe some of the confusion there is that when Jim and Marc first met, they were throwing around bunch of other ideas because Jim had done some really interesting things with on-demand television and some things with Nintendo and some other interesting projects, but eventually they came to their senses and realized that the web really was the right opportunity. By that we got in Illinois.

Brian: The browser kind of seems like it was the obvious step for them too because they already know how to do this. They’re going to get the band back together.

Lou: Exactly, so by the time we came together in Illinois, there was really all the focus to do something on the web, so there was two efforts there. We knew we’re going to lead with the browser. So the plan was certainly to holy re-create a new browser ground with stability, performance and targeted towards the average consumer and average computer, so to make it available for everybody and make the great product that everybody wants to use. And then the only kind of question that was remaining is how to really make money on this thing, so there was a lot of discussion about what we were actually selling and they eventually arrived at the model that we would create servers as well and sell the servers and give the clients away for free, so essentially the Razor and Razorblade’s model.

Brian: Right, so was that strategy worked out from the top? I’m curious to know like first of all, what was your job title at that point?

Lou: Almost all of us would just MTS, Member of Technical Staff. We were engineers and none of us really were that concerned about titles. We basically made up our own titles on our business card that sort of thing.

Brian: Right. That’s the sort of my question. The way to the NCSA guys describe it, coming up with different features, coming up with new things to add to that the next version; they are sort of kicking it around bull station style, is that how Netscape was at the beginning?

Lou: Absolutely, yeah, it was a very open and collaborative process. Everybody has a voice and the general consensus was that the best ideas will rise the top and you argue passionately for what you believe in, and this continue to make it for word progress, so not a lot of formal planning, meetings and that sort of thing. Essentially we’re moving so insanely fast, we would have these impromptu meetings when we hit particular roadblocks that would discuss the issue and try to really ring it out and then just move forward, so a lot of times you get to an implementation issue and the just grab some people. It might be 10 at night. Bunch of people go, yell at each other for a while. We like to say usually more cordial that come up with idea and then you started implementing that right away so we didn’t have traditional product management. We didn’t have a team of people that were often cornered keep thinking.

The advantage that we had was that we get all been there at the very beginning and spent years working on the web so we had all this experience already and were able to make experience decisions quickly, which led to certainly in my life that the greatest and fastest explosion of code and ideas that I’ve ever seen. It was amazing. All these people come in together with great ideas, work on this area for many years and had already produced something very similar, i.e. another web browser. Here we’re creating a new web browser from scratch, but along similar principles.

Brian: By the way, was that an ethic [SP] that we can’t use any of the old Mosaic code. We go to do everything completely from the ground up?

Lou: Absolutely yes. The idea was to sell this thing, so we needed to create something that wouldn’t be encumbered by any other copywriter, commercial problem. So make sure that we started clean and just move forward.

Brian: What were you specifically working on, was it the browser side or the server side?

Lou: I was the weird one because I had a little bit of a hand in both. I was doing all the crossed platform networking code and backend database and the communication flow within the browser. You think about. There was essentially three parts to each parts browser and I would say each browser; we had 17 different platforms to support. We had Windows and we had Mac, and we had 11 versions of UNIX and then within Windows and Mac, there was different versions, 64 and 32 bit and other things. They look like a lot of difference browsers in some ways. So there was front end code, which was the user interface.

There was low-level code, which was how the operating system interacts with your various networking libraries and that sort of thing. That was the responsibility of the front end teams and then there was the HTML interpreter if you will. It was the parser and how interface with UI elements on the screen. That was written by Eric Bina and then everything else that was cross-platform nearly. I was writing so the networking code, things like bookmarks, databases, history, caching, those sorts of things, settings. That is the stuff I was working on.

Brian: So at this point, what’s Marc Andreessen’s role? He is sort of covering in general, giving the marching orders or just keeping everyone marching in the same direction, what’s his role at this point?

Lou: Well, I think the plan was for him to be kind of technical leader when we started and he started in that role, trying to basically say we’re going to go. He is trying to make a technical roadmap. The reality was that he quickly got consumed with a whole lot of other stuff going on, especially the Public Relations effort and the ability to work with other company. We saw him paramount in the first month or two when he would come to the engineering meetings and such but then we didn’t see a whole lot after that. He got really busy doing other stuff not directly related to the client and server team.

Brian: And Jim Clark too, is he not necessarily there on a day-to-day basis. He’s out hiring people and things like that.

Brian: Well Jim was key in building the relationships hiring pretty massive team early on because as we felt that the client and server were on track. Jim was smart enough to recognize what we need to do. We need to build out these other services. So he started working on building out the product called the Merchant Server, which was something that could sell… actually do commerce on the web, so shopping cart model, various other things It was server specifically designed to help you write commerce on the web which was different than our content server and also fundraising and other things, having now been through that process many years on, I know how time consuming that is and Jim really executed that very, very well.

Brian: So you guys are able to get the beta version of navigator out in what six months?

Lou: I see. It was May 2nd essentially we were code complete about the end of August, mid September. So yeah, I think that I think the original beta came out like at the very early part of October if I’m correct. It was 20 years ago, so I don’t remember exactly, and it is about six months which is ridiculously fast considering how complex and how much code was over there.

Brian: And then the server was out a couple months after that too, so then you know right away the business plan is in place?

Lou: Yeah, technically we hosting the server right away but we didn’t release the server probably that was on a different release plan commercially for a little but technically it went out at the same time a client get because we were hosting off their ourselves.

Brian: So are you guys able to feel, you know, the rocket ship start to take off in the sense that are you aware of how popular navigator gets? I mean it’s obviously a year, two years on from when you’re doing things like Lynx and Mosaics, so the web itself is bigger, but what it did feel like once you finally get it out there and it’s starting to really take off?

Lou: Well, we didn’t have a long space between… essentially we were working on Lynx and Mosaic one day then we go to California start working on Netscape, the next day so we had about six months when we were just heads down working on our new implementation.

Brian: But ironically, at that point the web is doubling in size every two months, even that six-month period web’s way bigger than it was previous so.

Lou: Right. But we were still very much involved within the web development community because one of our one of our tenants coming from the Open Source community at University was to try to keep this whole thing open. That was a very important part of who we were and how our culture was so when we came up with new ideas, we put them out to the web community rather than just say, “Hey, this is our idea, we are going to just run with this.” So we had the idea that we wanted to continue to deal in and I wanted to make everything we did be part of the future standard. So when we came up with new ideas, we put them out there and say, “This is our cool idea. This is how we’re thinking of doing it. What you guys think.” We get feedback. We change what we are doing if people have better ideas than that and just generally try to put forth stop in a way that other people can use it to.

Brian: Like SSL, right. You guys worked to develop that but you immediately put it out there for everybody.

Lou: Exactly, but that the tenant was it’s only useful if everyone can use it and this rising tide makes everything go up. It was not the metaphor I was looking for but close enough. I know there’s a good metaphor in there but I forgotten it. SSL is a good example. There had been a lot of talk about these other encryption technologies and things that weren’t going anywhere. We knew that in order for web to succeed that people needed to trust that. We wanted commerce to explore on the web without security and trust, people aren’t going to buy anything, so we felt we had to put out the best possible security software and the best way to get everyone to use it is to give away an implementation completely free. So we made a reference implementation, gave the code away, and worked really hard to make it as good as it can be.

Brian: So you guys are all in your twenties at this point, so you routinely pulling me what you now the legendary 30, 40, 50-hour coding days and sleeping under your desk and that sort of thing?

Lou: It was bad. I was thinking recently about my diet was back then essentially 10 Mountain Dew, full strength, no diet. [Inaudible 00:34:47] food and I think my regular scheduled back then would be come in, work for about 20 hours straight. We had a little futon room, which is a little disturbing to think about now but it was a mattress in a conference room that was dark. I would catch 4-5 hours of sleep in at the office, wake up and do another 20 hours and then go home and sleep for like 12 or 15 hours, start the whole cycle again.

Brian: To be 20 again right?

Lou: Exactly. One of things about that time that made it special was we had we had a design pretty much figure it out because we already written for, so there was a great deal of actual coding to be done typically when you’re in a company, especially new company at startup, you spent a lot of time thinking very deeply about what the product should be and about certain design constraints because it is the first time you written a product like so we had a unique situation where tone of work to be done, just needed to get it done, so you really could work that hard and be productive. I wouldn’t recommend doing that to your average startup. Unfortunately a lot of start-up people think that is the way it should be done because all of the publicity we had. But we had a very special circumstance. To all the young coders out there if they’re listening, that is not a great way of getting work done in a smart, intelligent coding methodology.

Brian: That is funny when I have been doing the research on this; it is funny how much of the lure of how the Netscape environment was has become sort of like the template for the start-up. I mean even going back to you hear stories of these chair football games and having competitions with remote control cars and work hard play hard, sleep under your desk, that sort of thing. It’s almost like a startup culture took what you guys did and use it as a model.

Lou: Yeah and unfortunately the startup culture was defined by the press. The press just take whatever they think is most interesting, juicy and fascinating out of their limited time and they publicized that. Especially post Netscape 1998-1999, every startup was trying to do the things that they read about in magazines, but what they read about in magazines was nowhere near the reality of what Netscape was. That was just the popular media thought it was because that is what they were taking out of their limited time and publicized it.

Brian: Well, not only that but the whole I get big fast thing. I know that that’s a Jeff Bezos’ line but the whole strategy of let’s get out there and et ubiquitous and we will worry about money later. Again, especially in the .com days that was the playbook.

Lou: Well, my understanding that’s still a reasonable economical model or first motor advantage, took a lot of economists who was still supporting the model. It doesn’t matter your industry certainly whether or not that’s a viable model but certainly with a lot of different technologies that have switching costs getting to users first gives you the big advantage because the consumer doesn’t want to go try something different after they were locked into something they like.

Brian: So do you have the memories of the IPO?

Lou: Right, the IPO certainly a positive time in the history of the company. Honestly it was not a huge event for most of us because at that time we were still really, really heads down working on the browser and other Netscape products and the company was trying not to make it a distraction certainly remember not putting it any thought all into it. Prior to the day of IPO woke up on the morning of IPO and it was obviously shocked to see what it happened and see the run-up and that it’s really ridiculous amazing thing, but instead about a day thinking about it and then quickly got back to work. Certainly there was the thought in my mind that now there’s a hell of a lot of money available to my bank accounts, but worked really hard in a whole company from the top down was really focused on I’m saying let’s not let this become a distraction.

Let’s keep the main thing the main thing as Barstow like to say, and know that price evaluation is dependent on the work we’re going to continue to do. So we don’t keep the buses running on time, if we don’t keep working hard, that’s not going to mean anything, so there was a celebration. There was a party. They were relatively fast affairs and everybody got right back to work and work hard and try not to let that become a big distraction. It wasn’t really until a fair amount of time later when liquidity kicked in, some other events happened that really dawned on any of us,” Wow we got a lot of money.”

Brian: The Porsche starts showing up in the parking lot.

Lou: Honestly, the Porsche didn’t really show up until we started acquiring other companies. The founders, the initial crew from NCSA and I and some others, we kept each other very grounded. None of us bought any fancy car. We kind of joked that we’re going to drive beaters for the rest of our lives. Just to disprove the whole myth that you have to you have to become [inaudible 00:41:13]. Most of us drove very reasonable cars for many, many years. I didn’t buy my first fancy car until after I left Netscape and we try to keep each other just grounded and focused knowing that that those are the things are merely distractions in our life and what made us special, what made us great, was our ability to have these technical achievements and if we give that up, what are we?

Brian: You left Netscape is it 1998 to do Epinions, is that right?

Lou: Yeah, I left at the end of ‘98 right at the AOL acquisition.

Brian: Right. That was my next question. In retrospect, historically it goes down to everyone says Netscape got crushed underfoot by Microsoft, the browser wars and all that stuff. I mean, do you feel like that there was anything Netscape did wrong, could have done differently. Again, looking back on it 15 years later, I don’t know how that much time gives you perspective on that sort of thing, but were you guys aware that Microsoft was coming for you and things were starting to get bad at some point?

Lou: Absolutely, yeah. It was hard to escape unfortunately and back in those days, I had a fair amount of anger about the whole thing. I will preface some of this as saying that Microsoft was eventually found guilty of significant malfeasance and that it is largely because of the pressure that we brought to there and it was unfortunate that we had to be the victim of that. It was also pretty sad to see the next administration come in and essentially dismiss all of the penalties against the company. The net result was as Netscape grew, we diverted from our original business model little bit because people really wanted to pay us for the client, so we started to generate a substantial amount licensing revenue from that the clients, from businesses especially Fortune 500 businesses. They were paying us a lot of money. We were still selling the server, but we’re also selling a significant amount of the browser.

About somewhere close half of our revenue was coming from that and we use that money to grow the company very quickly and start diversify, what Microsoft did was they had a strategy to essentially take away all of our revenue on the client side. So they originally said, we’ll just keep the browser away for free and they tried that for a couple of versions. They originally bought a version of the browser from, and put that out and start working on their own. And they try to giveaway their browser for free for really long time and nobody would take it because it wasn’t particularly a good software. And over time they improve their software but they still weren’t getting a lot attraction and giving away for free, so they started essentially paying people to start using their browser.

So there was many, many examples where we would close a big deal or be close to closing the deal, we find out that that no we’re not really to get the money from that deal because somebody from Microsoft came in and offered to buy a division of that company for an obscene profit so that that large company would start using Microsoft browser instead of our browsers. So instead of us getting $20 and $30 million on that deal, that company got paid $20 or $30 million to not use us. That’s little disheartening but we were still doing well. We still had 90% of the market and making traction. The biggest single event that really triggered downfall of our company was the switch of the AOL browser from Netscape to Internet Explorer. At that time AOL was 35% of the Internet traffic because a lot of people in the US were on AOL dial-up and they don’t get a choice, they get whatever browser AOL giving them and they were using our browser because it was the best.

This is all well-publicized Microsoft offered AOL a place on the desktop if they would switch and that’s worth billions of dollars and legality there was that time one monopoly to another business as when Microsoft was found guilty of abusing at that time, but what it what it really did was it changed the nature of the browser percentages, so went from 90% Netscape to more or less 65, 70% Netscape essentially overnight. And what that meant was that the content producers, the guys creating all of the content on web before we just write new features for Netscape and admit that we always had a lead. We’d continue to come out with new software and that was better and better and when 30% of the Internet is now suddenly Internet Explorer down all the content guys saying, “Oh now I have to pay attention to Internet Explorer. Now we have to create content that works equally good in both,” and what they did was it made us a commodity and when you’re commodity, i.e. you can use either it doesn’t really matter.

Then you’re going to lose to the big fish in town. In order for small company to succeed against a big company, you have to have a product advantage, you got to have uniqueness and differentiation, and once you become a commodity than all you can do is give it away for free or have it for a cheaper and you can’t be cheaper than what Internet Explorer was which was free and coming with everything else, so making us commodity essentially meant the death of our client business, which meant for all intensive purposes, we were now no longer the mover and shaker on the Internet anymore.

Brian: Even despite the fact that most of your revenue is coming from the clients coming from the servers.

Lou: Right but 50% of our revenue is from client. To switch 50% your revenue in one year is herculean task. It put insane pressure on us and we started behaving a little bit dysfunctional. That company decided wanted to become a groupware company all of sudden, so we are suddenly focusing efforts on e-mail and other kinds of groupware features which is very distracting from our primary mission, which was web browsers and the web itself. I think in retrospect it would be much better to stay focused on just the web; clearly there is revenue there. But at the time we were scrambling because we are under intense financial pressure. Once you grow is really hard to shrink back down, it’s only go up, should only go up in those cases.

It became very, very difficult. We recently had our share of other interesting challenges that at the time felt it really, really serious but in my retrospect, having been 20 years in the industry right now we’re still doing a lot of things really, really well as a company as an engineering company and other things, could have done better, but that certainly in a normal company, another things that we were being badly would kill the company. But as our as a client revenue shrank, we were under intense financial pressure and the company started to have this really kind of doom and gloom it, and especially at the beginning of 1998 when we had to do layoffs and other things.

Brian: You said earlier, you were bitter about it for a long time. Do you feel slightly differently about it now?

Lou: Well time heal those wounds, but I was really, really angry at Microsoft and Bill Gates in particular, for essentially killing the company that I helped create all my blood, sweat and tears into and I get why they did it. They felt threatened but at least if they done it fairly, I would have felt a little bit better about it, I still would have been pretty angry but to know that they had broken the law to do it. As I felt then really taking food from the mouth of my children was really made me angry. They said out specifically to kill our company and I think that would make anybody angry.

I still have some money from the experience. I’m not going to be in a trailer park anytime soon, and I’m very happy for the experience and in some ways I’m really quite happy that I didn’t become some mega- billionaire from the experience. Because I’d been able to go on and create other companies and grow and learn and become a much better engineer, and better manager, leader, builder other companies. I don’t know that I would have had the same incentive to do that if we had simply gone on and become Google sized or something like that.

Brian: Mm-hmm. Switching horses here a bit. I wanted to get back to you personally a little bit because there are so many basic features of browser technology and web technology that you had a hand and you were therefore, you know, proxying SSL, that sort of thing but a couple in particular, you become as you put it somewhat infamous for the browser cookie.

Lou: Yeah, I guess you want me to start about cookies then.

Brian: I mean a little bit and I mean you know people have hated advertising on the Internet from day one, but obviously we couldn’t have gotten to this place if we didn’t have advertising and in your blog post that you have about it. It was a really thoughtful way that you did it like you put a lot of thought into it when you first came up with it. I don’t know if some of the articles make it seem like it some sort of albatross [SP] or something but somebody had to do it and you did it in a thoughtful way I think.

Lou: Yeah, we certainly cared a lot about privacy and there had been a lot of discussion about other mechanisms for adding state to the web. As so when I design cookies, it was really with the thought that we’re going to add some state to the web but as protected as we possibly can of our privacy across the web. So cookies would enable us to have a memory so that when we returned to sites we can interact with that site in a way that it remembers us and can have a much richer interaction but at the same time wanted to protect against tracking across all websites through the sharing of unique IDs. As it is well-publicized, we weren’t able to achieve all those goals. That there’s some amount of tracking was enabled by essentially having a whole bunch of websites work with other centralized websites to do this collection but also as I’ve is said in another blog posts and such, in pretty much any model that you have some sort of memory, and I would preface that this by saying that some amount of memory is absolutely necessary for a reasonable experience on the web.

So any model which introduces memory will suffer from that same problem, the ability to collect some amount of information in the future. So there isn’t really any way to get away from this except get rid of all the features that we know and love about the web. So we have to deal with this problem in some way and cookies give the much of the power back to the user, so users who really care about strong privacy protections can go in and change their settings and changed how they how their web browser works so that they can take control back. And one of the things that I would say is that good technology stands the test time and people have look to cookies and examine cookies and try to come up with better alternatives for 20 years and it’s still the same old cookie, meaning that nobody has come up with anything better yet. I thought about it a lot. There are some minor improvements we can but the basic fundamentals tenant of the cookie is still a good one and people get I kind of benefits from it.

Brian: I think actually like I said I thought was a reasonable argument that you made in the blog post, which I’ll put a link to that on the post page as well but answer for the blink tag.

Lou: Well, I think my blog post says it all. We came up with kind of a funny thing and then it was introduced by the other engineers as an Easter Egg, a functional Easter egg. Unfortunately the functional Easter egg leaked out and people start using it so clearly there was some demand there. Although not necessarily enjoyed by all and we finally did give you the ability to share blink off and that sort of thing but it was a funny joke that get a little out of control.

Brian: I kind of agreed with a commenter that, “Blink was nearly as annoying as the Marquee.” Do you remember the Marquee tags?

Lou: Well, you know, all those things eventually culminated in the invention of the animated GIF.

Brian: That’s funny that you said that, I was going to bring that up to. How were you involved with that like making that a standard in the browser or what was the deal there?

Lou: We had today decided to add Java into the browser as a standard feature. Basically a plug-in that would include with the browser and Java had all this great promise as being a something a running code within the browser and sandbox safe environment. The problem was Java at time had a horrible implementation and took about 30 seconds to boot, just like to start up. So any Java app comes up in webpage, 30 seconds later the Java App starts up after grinding your computer to a complete halt so it was not particularly wonderful experience and I found as I was surfing the web after Java release seems like the only purpose that people were using Java at that time was to put scrolling banner ads, and flashing things up above content, so that people would notice the banner ad and I was just really annoyed every time until webpage, it would take 30 seconds for the thing to start up and it was killing my computer.

So I remember having this conversation with the guy who is writing our imaging code Scott Furman and he told me that gifs has ability to do the animation thing and it was really cool. He showed me how this could work and at that time, I was like, “Oh, this is awesome. We should put it in.” He was like, “Nah, nobody wants it. It’s a lot of work. We have to do all this things.” So we kind of let it go and then when I saw Java was only doing basically just stupid animation and it was killing my computer, I went back over to Scott and I said, “Scott, we got to do this.” He was resistant. I just kept on going every day. Every time I would see Java come up, I will be like “Scott, we got to do this, we got to do this, we got to do this.” After about a month of pestering, he finally relented and built the animated gif code into the browser for the next release and essentially the old ad Java disappeared in one release because everybody said, “This is much better to do banner ads.”

Brian: Yeah, that’s funny. The first thing that we did was every ad that we ran for three years were animated gifs.

Lou: Exactly and so it was really my anger at the bad implementation of Java that caused me to just go insane on that thing. In some ways it probably killed Java because it created less incentive to go fix Java to be faster because people stopped using it essentially. We were just incorporating Sun’s code. If they had just got around to making Java a little bit faster, the Java interpreter. It probably would’ve been fine, but since they never got it run to doing that, Java pretty much died as a client side language on the web and we were also working on the Javascript which did all of the things that Java hoped to do within the browser.

Brian: Well, could you possibly have imagine the afterlife that the animated gif had these days, where it would be read without it?

Lou: Exactly. It’s a fun name. I love animated gifs most time. It’s nice to see that we don’t have all those quite as annoying advertisements as it used to be with the craziness that early days brought. And now that we have video formats and everything else, we’ve gone beyond what the animated gif originally set out to do.

Brian: Right. Is the FishCam still running? I thought that it was.

Brian: Yeah. If you go to the fishcam.com, you can see it. I got wave in the camera after we’re done. It would come up on the 20-year anniversary. I think the FishCam first went live somewhere in August, September got a timeframe of 1994 or so. I don’t know what I am going to do on 20-year anniversary there but something fun.

Brian: Well, that segs me easily to my final good morning America style puff questions for you, which are essentially you know it is 20 years now, I feel like I wanted to ask all of you guys that were there at the beginning of the stuff like? Is the web and the Internet what you were envisioning at the time? Are you disappointed by what it’s become? Is it more what you could have imagined? Is it exactly what you have imagined?

Lou: Well it’s certainly way beyond what I could have imagined because the way people have used it in businesses that are completely transformed now, I’ve never would’ve imagined. The idea at the founding of the company was to create a platform where people could do things that were extraordinary way beyond what we could think of. We would actually sit in meetings and say, “Okay that’s a good feature, but how we may it so that people could do stuff that we can’t even imagine. Let’s not limit this to our own imagination. Let’s make the building blocks capable of building something way beyond, so make sure it fits the laggards.” It was partly the design of cookies that made more general than it needed to be so that people would do more with it than just what I was imagining and the design of JavaScript. The design of our HTML elements were designed to create building blocks that we built into something that is extraordinary.

And I’m unbelievably proud of what we were able to create. If you look back at the history, at the time period between 1994 and 1995, when we started the first two years of our developments, essentially every major piece of technology, which drives the web today was invented in that time period by relatively a small group of very passionate engineers and I’m just humbled and I just overjoyed that I was part of such a special team that worked really, really hard to create the initial technology that is exploded in something so amazing.

Brian: Does it feel like it’s been 20 years or this coming up, is it coming up faster than you would’ve imagined? What does it feel like 20 years on now?

Lou: It definitely doesn’t like 20 years. Sometimes I wonder where all the time comes. I have been enjoying my life and trying to do as many things as possible, and I can’t believe 20 years has gone by. I recently seen several of the founding team members and we don’t look that different honestly. I guess that is just the matter of perspective but…

Brian: You never looked that different when you look at the mirror, do you?

Lou: No.

Brian: You still see the 10-year-old or something looking back at you?

Brian: Yeah, everybody is doing well and I spent a bunch of time with Jim recently and he is unbelievably vibrant. He is expecting a second child and living life to its fullest. We have these amazing conversations and talk about. We don’t focus on the past don’t a lot. We’re thinking about what will be another great company to start. How is Mobile technology transforming our lives and various things, just new ideas and loving where the world is and where it can go?

Brian: Well that sounds like a good place to end. You are at zetta.net now correct?

Lou: Absolutely.

Brian: And just a little bit about Zetta first.

Lou: We are a leading provider of off-site data protection and disaster recovery services for small to medium enterprises.

Brian: Excellent, well I’ll let you get back to that. My thanks definitely to Lou Montulli for taking the time to talk to us.

Lou: You’re welcome. Thank you very much for having me.

Listen:

[…] on Montulli’s podcast interview to hear the full […]

[…] Lou Montulli […]

What a very interesting interview. Great work Brian. I recently became interested in the early work and legacy of Lou Montulli, It was so wonderful to share the air with you guys and listen to a living history of Lynx, Netscape and the Web in general.

This was my first podcast experienced from Internet History Podcast. Fair to say you’ve “hooked” another – Thanks!

[…] An Interview With Lou Montulli – Internet History Podcast […]