This Sunday, August 9th, marks the 20th anniversary of perhaps the seminal moment in modern tech history. On August 9th, 1995, Netscape Communications Corporation went public.

Regular listeners know, I began this project last year by collecting oral histories from a good chunk of the original Netscape engineering team (read a summary oral history here or listen to all the oral histories here). We all know that the Internet, and even the web, predated Netscape. But as the first Internet company that truly mattered, I chose to begin this project with Netscape because it was absolutely the harbinger of the modern technology revolution that has transformed all of our lives over the last 20 years.

Netscape was not the first Internet company, of course. It wasn’t even the first Internet IPO. Most people give that title to an early ISP, PSINet (although, cases can be made for RSA Security, CMGI, Network Associates, or even America Online, which all predated Netscape’s IPO). It might seem a bit silly to say that a stock offering marks a key milestone in the history of technology, but that would be overlooking the shear, audacious, groundbreaking value of being first to this particular revolution. Quite simply, Netscape’s IPO was the event that signaled to Silicon Valley, to Sand Hill Road, to Wall Street, to Madison Avenue and to Main Street that something utterly new and transformative was on the scene. And the revolution that Netscape kicked off hasn’t stopped even 20 years later.

Ghost Valley

When Marc Andreessen first got to Silicon Valley in early 1994, it felt to him like the place was kind of dead. “Everyone seemed rather morose, kind of looking at each other and asking why nothing exciting seemed to be happening in the Valley anymore,” Andreessen would later say.

Indeed, the Valley was ready for a generational turnover. The 70s and 80s excitement of the PC era had long since passed. There had been brief fads (bubbles, even) for artificial intelligence tech, CD-ROM tech and especially pen-based computing. The failure of the Newton and Go Corporation put an end to the latter; the web would kill CD-ROMs; we’re still waiting on AI…

Tech-based venture capital was somewhat moribund. The early 90s recession hit the valley hard. PC shipments even fell in 1991, for the first time one record.

But when Jim Clark recruited Marc Andreessen to “do something” on the web, the stage was set for a new kind of company, a new way of doing business. Clark came from the world of machines and hardware (Silicon Graphics) where development schedules were measured in years—even decades—and where “doing a startup” meant factories, manufacturing, inventory, shipping schedules and the like.

But Andreessen promised something comparatively simpler. Long before he said that software would eat the world, Andreessen intuited that in an internet paradigm, you could dream up a product, code it, release it to the ether and change the world all the same. He and his college buddies had already proven that with the Mosaic browser. In the web world, development schedules could be measured in weeks; if you released a version update, people could just download it.

Web 1.0 veterans such as myself like to grouse about how much easier, simpler and—most importantly—cheaper it is to launch internet companies these days. But really… think of how different it was to launch Netscape compared to, say, Compaq… or even Microsoft. It’s not that Netscape discovered, or even invented, the modern methods of launching web-based, digital software startups. Netscape was, however, the first to put these methods into practice on a major scale. And Netscape was certainly the first to do so successfully.

So many details about the culture of the modern tech industry can trace their roots to the Netscape story, whether accidentally or by design. A lot of the key innovators of the 1980s PC era were tech industry veterans or West Coast natives. But almost the entire Netscape crew that Jim Clark recruited over from Mosaic were midwestern kids. Today, kids from around the world dream of heading to the Valley and finding their fortune. The original Netscape crew were the first to make this journey. They didn’t know they were the vanguard of a new-fangled gold rush. They were, literally, corn-fed. They were used to making six bucks an hour for their coding and had little inkling software development could pay more than that. When Jim Clark dangled a high-six-figure salary in front of them, complete with something called stock options, they almost thought they were being punked.

“He [Jim Clark] basically gives me a letter with the salary and a number of stock options,” Netscape founding engineer Rob McCool told me. “I didn’t even know what stock was at that point, but I knew that the salary was enormous.”

Accidental Trendsetters

Engineering has always been a pursuit that lends itself to intense bouts of work, of long bursts of productivity where you come up for air and realize you’ve been coding for days straight. But that wasn’t necessarily the culture of the Valley before the Internet. The Valley of the Hewlett-Packard era was closer to a mid-20th-century collared-shirts-and-ties work culture than the pizza-and-caffeine-and-t-shirts ethos that Netscape ushered in. But we can’t blame Netscape for that. Even though so many of the breathless news-clippings from the time focused on the all-nighters and the frat-house hijinks of the Netscape offices, these were, after all, kids fresh out of college. That’s just what they did. That’s just what they knew. It was only the intense media focus on their work habits that turned that sort of thing into something that was de rigueur for the startup “lifestyle.”

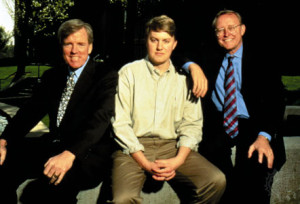

Original Netscape team members: Chris Houck, Aleks Totic, Marc Andreessen, Jon Mittelhauser, Jim Clark, Lou Montulli, and Rob McCool. Photo Credit: Andy Freeberg; Illinois Computer Science Dept.

Netscape veteran Lou Montulli told me that startup culture was defined by the press, using Netscape as the template. “The press just take what they think is most interesting, juicy and fascinating out of their limited time and they publicize that. Especially post-Netscape, in 1998, 1999, every startup was trying to do the things they read about in magazines.”

Another Netscape engineer, Alex Totic, said: “We [were] working around the clock because that’s what you used to do before. Four years later, five years later, the entire valley [would] be living the same lifestyle. But those people actually have lives. We really didn’t have any lives outside of the office so of course we’re going to be at the office all the time! I mean, I had no furniture. Why should I ever go home?”

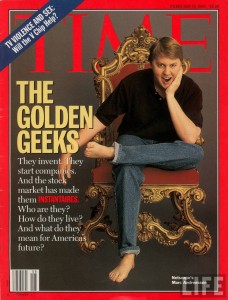

Another thing that’s funny to read in all of the media hype from the time is the “gee-wiz, these guys are filthy rich overnight” stuff. Today, we’re used to the idea that a kid can code an app in his dorm room and 6 months later be worth a billion dollars. But in 1995, that was definitely not a thing. So much of the coverage from the time has this sort of incredulous tone around the fact that these are know-nothing kids in their twenties and now they’re paper millionaires overnight! In Marc Andreessen’s famous cover article in Time Magazine, they marvel at the fact that he was suddenly worth a cool $58 million dollars.

In that same article, Time felt it had to educate its readers on the basic concepts of the phenomenon:

The wealth comes from initial public offerings of stock, or IPOs, which are experiencing an unprecedented boom in the great bull market of the last two years. As the stock market has smashed records, more and more private firms, particularly technology companies, have decided to raise cash by selling equities to the public. More capital was raised in IPOs by emerging high-tech firms in 1995—$8.4 billion—than in any other year in U.S. history.

Before Netscape and before the dotcom era, entrepreneurship hadn’t been “cool” in America for a long time. For most of the 20th century, kids aspired to be rock stars, athletes, stock brokers or maybe astronauts. But nobody thought that starting a business could turn you into a rockstar. Heck, it wasn’t exactly conventional wisdom that being an entrepreneur was a decent path to fabulous wealth. Netscape’s IPO was the first event in a chain of events that would bring that notion into the zeitgeist.

Trailblazer

It’s funny now to think that Netscape Navigator could be considered a monster success because it could count its audience adoption in the tens of millions. But that’s because we live in a world of hundreds of millions of iOS users and billions of Facebook users. In 1994-95, the online population of the entire planet could be measured in the tens of millions. Netscape found itself with 90% share of a market that was already growing exponentially, and could only continue to do so until every human on the face of the Earth was plugged in.

There’s something to be said for identifying a tidal wave of history and standing in front of it until you can ride it all the way to shore. But there’s also something to be said for being in the right place at the right time… even if you have no idea you are.

As the Barron’s reporter Maggie Mahar told me, Netscape and the dot-com bubble era it ushered in was (coincidentally) exactly the moonshot Wall Street had been waiting for. By 1995, the stock market was entering the final stage of an epic bull market that had begun in 1982. The rise of 401ks, combined with the return of laissez faire economics and Dow 4,000 (!) had set the table for something crazy to happen. Bulls were hungry for some nitro to extend their run. The Internet, with its endless possibilities, with its this-is-a-new-paradigm, this-time-it’s-different fervor was exactly what they were waiting for.

On the day in question, Netscape shares were originally set to be priced at $14 per share. At the last minute, the price was lifted to $28 per share. When the market opened at 9:30 AM Eastern Time, Netscape’s stock did not open with it. Buyer demand was so great that an orderly market could not immediately be made. Interest from individual investors was so overwhelming that callers to the retail investment firm Charles Schwab were greeted by a recording that said: “Welcome to Charles Schwab. If you’re interested in the Netscape IPO, press one.” At Morgan Stanley, one retail investor offered to mortgage her home and put the proceeds into Netscape stock. The first Netscape trade did not hit the ticker until around 11:00 AM. The price of that first trade was $71, almost triple the offer price and more than five times the price from the night before.

As August 9 also happened to be the day that Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead died, a joke made the rounds on Wall Street: What were Jerry Garcia’s last words? Answer: “Netscape opened at what?”

Over the course of that day 20 years ago, Netscape, under ticker symbol NSCP, reached $75, before ending the day at a still respectable $58.25. Netscape had only existed as a corporation for 16 months. Since its inception, it had generated revenues of only $17 million. It had nothing in the way of profits on its balance sheet. But at the end of trading that day, the stock market valued the company at $2.1 billion dollars.

Quite simply, it had been a long time since Wall Street had seen something like this. The 1980s had been about Leveraged Buyouts and Junk Bonds and Masters of the Universe. Somewhat missing from that milieu? Creating new industries from scratch. Things like that hadn’t been common since the go-go 1960s, or even the 1920s, when industries like air travel, radio and consumer electronics were first born.

Certainly, it had been a long time since companies “popped” on their IPO debuts. As much as anything else, it was the overnight ascent of companies like Netscape that blew people’s minds. It had taken 12 years before you could begin to talk about all the millionaires Microsoft had minted. Netscape had done it in 15 months.

We can blame Netscape for starting the chain reaction that introduced IPOs and “first-day pops” and CNBC into our everyday conversation. But Netscape fit into a very specific kind of wish fulfillment for investors. For the first stages of the 1980s-90s bull market, there were two stocks that everyone kicked themselves for not getting in on early: Microsoft and Walmart. Netscape promised to be a next generation Microsoft, a software company with fat software-industry margins, and with the promise of creating a “platform” that an entire industry would have to play on (and pay tolls to, ala Microsoft). The web browser could be that next generation platform. As Marc Andreessen, perhaps unwisely, but so famously said, Netscape might become a company that could turn Windows into “a mundane collection of not entirely debugged device drivers.”

(Parenthetically, Amazon has been trading on the promise of being a next generation Walmart for almost two decades now.)

This was heady stuff. Investors wanted in. They didn’t care that Netscape was not even two years old at the point of going public, and had nothing in the way of profits (and frankly, not that much in the way of revenues). This was the first time in a long time that a skys-the-limit stock had come along. The only thing that limited what Netscape could become was your imagination. Again, a lot of the media “buzz” at the time was about this crazy, young, unprofitable company that dared to IPO on a promise and a dream. Companies simply didn’t go public so quickly. Not in those days. Not until you could at least prove your concept with, you know, actual bottom line black ink.

Why was Netscape so eager to IPO so quickly? To this day, some people think it was because Jim Clark wanted to finance a new yacht or because he was eager for redemption after his murky exit from SGI. But whatever the real reason, Netscape’s IPO blazed a trail that said, yes, our idea might change the world. And everyone was ready to drink that particular brand of Kool-Aid.

Netscape’s IPO taught Wall Street and Silicon Valley a valuable lesson. The web, and the Internet in general, were a wild-west proposition; a land grab. The key was to get there first and dominate before competition could even notice. Andreessen’s platform strategy seemed to be a proven concept; ironically, it was one proven by Microsoft. Early profits were not important at all. Revenue was important, but not entirely a requirement. The more valuable thing was to show a sense of “Internet speed,” the ability to be nimble as well as a willingness to chase markets and market share; to sense your moment of opportunity and just fucking go for it.

As the journalist and author Michael Lewis described it later, “You had to show that you were the company not of the present, but of the future. The most appealing companies became those in a state of pure possibility.”

Limitless Potential

The bottom line was, no one knew how big this Internet thing could be. Netscape showed that it could be very big indeed, but the sky was probably not even the limit. Anything you could think up could be virtually created on the net. Anything, and any market that might exist in the real world, could be duplicated on, and possibly disrupted by, the Internet. The Internet was exploding in growth. But even at the beginning of 1995, there were only, maybe, 20 million people online. The possibility existed that someday everyone in the world, all 6 billion or so people, would be online. You don’t often get markets with growth possibilities like that. Not even once a lifetime. Possibly the only other time it had happened in the history of capitalism was during the Industrial Revolution. When entrepreneurs and financiers internalized that lesson, the boom was well and truly on.

We all know, of course, that Netscape was not destined to be the big winner of this revolution. Some will wonder how “important” or “influential” Netscape as a company truly was, since it only existed as an independent company for about four and a half years.

But to them, I would say: sometimes being first means the tidal wave of history simply drowns you. Even if it does, that doesn’t mean you didn’t blaze the trail.

Netscape, the company, could never quite figure out what to be. Netscape (or, Jim Clark specifically) introduced the idea of “Internet Time,” the concept that companies could move, and iterate and innovate at lightning speed. And to this day, that sense of relentless iteration is the lifeblood of the startup world. But Netscape was never actually very good at it. It was like a newborn foal that couldn’t quite get its footing before it already had to run for its life.

Could web browsers have been a valuable software package like operating systems or productivity suites? We’ll never know, of course, because Microsoft leveraged its monopoly position in both operating systems and productivity software markets to drive the price of web browsers down to zero. Down to table stakes for modern software. I acknowledge that Netscape kinda-sorta gave away Navigator to a ton of people, including me. But that was their biggest problem. They were never sure what their business model was, exactly. At first, they were a razors and razor blades company. They wanted to give away the browser to make their money on the servers. At other times they were pursuing a more traditional licensing model. Microsoft killed that, of course. Then, they pivoted to a groupware model and created a software suite complete with email and other clients. There was even the time when Netscape pivoted to become a web “portal.”

Maybe the whole problem was that Netscape itself focused too much on becoming the next Microsoft. In 1995, that seemed like the big opportunity. At that point in time, Microsoft basically was the technology industry. Few at the time could imagine that this was actually Microsoft’s highwater mark. Few could see that the tidal wave of history would wash over them too. They say you’re always fighting the last war. Sometimes, perhaps, you’re fighting the last Godzilla. Netscape thought it could supplant Microsoft’s Windows platform. But in reality, it took 15 years, and the rise of mobile to really do that. They simply shouldn’t have bothered. They perhaps should have just ridden the wave of the Internet Revolution which was destined to defang Microsoft anyway.

One of the Netscape engineers, Rob McCool, told me this: “What killed Netscape is that we were revolutionary and different for a software company, but at the end, we thought of ourselves as a software company. And that, more than Microsoft, is what killed us. I walked around the halls of Yahoo [in the late 90s] and I remember one day looking around and realizing, “Hey, you know, they use the same type of offices, the same kind of cubicle equipment, they use everything, but they’re still here and we’re not. Why is that?” And the reason was, they were more flexible to what became the new rules of software. That you can’t just package something up in shrink wrap and charge $10,000 for it and that’s the model. You have to do more incremental things. And you have to be able to charge people in new and innovative ways.”

The web really was a revolution that changed the whole game… scrambled the entire chessboard. Netscape was the company that heralded the arrival of this revolution and the irony was that the changes it ushered in were too much for even it to survive. But that doesn’t change the fact that Netscape was the trailblazer.

So, on this 20th anniversary, pour one out on the ground for Netscape. They might not have lived to tell the tale, but the tech world we live in today wouldn’t be what it is without them.

[…] The IPO also stimulated the dot.com boom of the late 1990s and it has come to be called the “big bang” moment of the […]

[…] to as the big bang of the internet era, Netscape’s 1995 IPO was groundbreaking because the company was the first to successfully launch […]

[…] to as the big bang of the internet era, Netscape’s 1995 IPO was groundbreaking because the company was the first to successfully […]

[…] fut un flop commercial, mais quelle histoire! Elle a changé la face du monde. D’ailleurs, avec Netscape et son entrée en bourse en août 1995, l’histoire du Mac et sa descendance sont probablement les seules du secteur des TI qui ne fasse […]

[…] Capital’s Avichal Garg, harkening back to the Internet browsing company whose success and 1995 IPO ushered in the modern web. (Coincidentally, Netscape co-founder Marc Andreessen is on Coinbase’s […]

[…] as a big-time validator for Bitcoin and other popular cryptocurrencies. You could liken it to the Netscape offering which captivated the world in the mid-1990s by boosting the visibility of the […]

[…] a big-time validator for Bitcoin and different common cryptocurrencies. You can liken it to the Netscape offering which captivated the world within the mid-Nineties by boosting the visibility of the […]

[…] a big-time validator for Bitcoin and different common cryptocurrencies. You would liken it to the Netscape offering which captivated the world within the mid-Nineties by boosting the visibility of the […]

[…] validator for Bitcoin and different fashionable cryptocurrencies. You would liken it to the Netscape offering which captivated the world within the mid-Nineties by boosting the visibility of the […]

[…] serve as a big-time validator for BTC and other popular cryptocurrencies. You could liken it to the Netscape offering which captivated the world in the mid-1990s by boosting the visibility of the […]

[…] as a big-time validator for Bitcoin and other popular cryptocurrencies. You could liken it to the Netscape offering which captivated the world in the mid-1990s by boosting the visibility of the […]

[…] McCullough, Brian. “20 YEARS ON: WHY NETSCAPE’S IPO WAS THE “BIG BANG” OF THE INTERNET ERA̶…. http://www.internethistorypodcast.com. INTERNET HISTORY PODCAST. Retrieved 12 February […]

[…] to work and write software and build gizmos,” continued Andreessen, himself the brain behind the Netscape browser. The Harvard Business School grads, meanwhile, will eventually follow only when there’s enough […]